Scotland – The fight for home rule a stepping stone to independence

The movement for home rule evolved in the 1980s and 1990s with the Scottish Constitutional Convention emerging as a key player.

The Convention published the Claim of Right for Scotland, asserting the right of the Scottish people to determine their own form of government.

The Convention produced a report with detailed proposals for a devolved Scottish Parliament, which ultimately led to the 1997 referendum and the establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999.

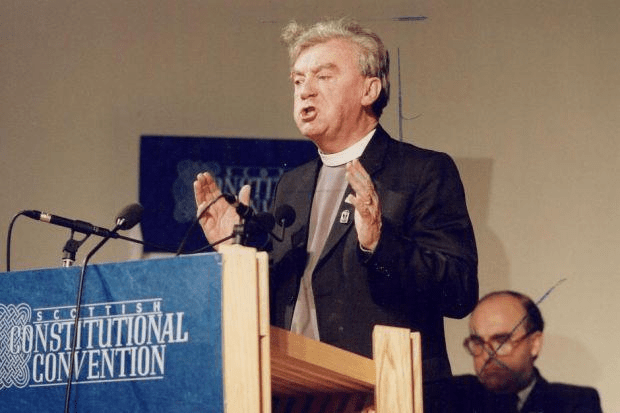

The Scottish Covenant and the subsequent Constitutional Convention was led by Paisley born, Canon Wright, an inspirational figure who played a crucial role in the long-term push for devolution and the establishment of a Scottish Parliament.

Canon Kenyon Edward Wright -Born: 31 Aug, 1932; Died: 11 Jan, 2017

Canon Kenyon Edward Wright was born in Paisley, the son of a technician for the major local employer J&P Coats, he attended Paisley Grammar, studying later at both Glasgow and Cambridge universities.

He was the man who had possibly the strongest claim to have been the godfather of devolution. He will be remembered for his role in cajoling disparate Scottish opposition groups to work together and moulding a single coherent case for constitutional change.

He was invited to lead the seemingly impossible task of creating a consensus that was to drive the path towards a second devolution campaign and the resulting creation of the Scottish Parliament in 1999.

In doing so, he set a mark for political campaigning in Scotland. By the second referendum, he had even brokered the return to the fold of the Scottish National Party, which had boycotted the convention.

The arrival of Canon Wright to the political stage, as executive chair of the Scottish Constitutional Convention, kick-started the home rule campaign with an assertion of the sovereign right of Scots to determine their affairs. Although hardly a household name, he was recognised then as an articulate Church figure and an energetic campaigner fascinated by politics and community activism.

At 23, newly married, he travelled with his bride, Betty, to India as a Methodist missionary. Their sojourn was to last 15 years.

In 1970, he returned to the UK as director of urban ministry at the prestigious Coventry Cathedral. He was quickly promoted, and directed the cathedral’s international ministry.

Now a Canon, he returned home to Scotland in 1981 as general secretary of the Scottish Churches Council, an appropriate post for an Episcopal priest well used to working with other denominations to achieve shared goals. He was still in his forties and keen to make his mark. His arrival came as the Christian churches were experiencing decline. A once notably pious nation was lapsing rapidly into secularism, even agnosticism.

Inspired by the efforts of Roman Catholics aiding the Solidarity movement in Poland and at odds with the right wing politics of Margaret Thatcher which she proudly espoused to the General Assembly in her infamous Sermon on the Mound. He decided it was time Scots had a voice in decision making within the UK

The Conservatives had long opposed devolution, and relied on the internecine warfare between the opposition parties – particularly Labour and the SNP – to continue what was effectively “direct rule” from Westminster.

In this context, Canon Wright made his now-celebrated comment: “What if the other voice we all know so well responds by saying ‘we say no, and we are the state’? Well we say ‘yes – and we are the people’.”

When he arrived, the Campaign for a Scottish Assembly had produced the Claim of Right for Scotland, which was to be the basis of the convention’s work.

Canon Wright pulled together its constituent partners, including political parties, trade unions and other interests. He did so with a certain style, and produced the convention’s final report in 1995. Its main points were adopted by the New Labour government in 1997, and approved by referendum that same year.