Robert Harley and England’s 1707 Union with Scotland

Commissioner Harley, leader of England’s 31 strong group of commissioners went away from the negotiations to complete a number of commitments but before doing so he, (typical of his need to control the agenda) tried to persuade the Earl of Mar to convince Carstares that it would be prudent to leave any reference to religion out of the negotiations.

Aware of the keen interest of the Dutch in the outcome of the discussions he took the time to meet with and brief England’s relevant foreign service ambassadors and personally briefed the Dutch Pensionary of the progress being made “to bind the Scots forever by the benefits they shall enjoy.”

The process of negotiating the treaty had been hard work for Harley and his team. Ratification by the Scottish estates proved to be just as difficult and to be sure of success in that process he had to revert to the use of his spies who had been in Scotland for some time and were aware of local issues and how to deal with them.

It was Defoe’s contention that based on population Scotland should be represented in parliament by 85 members. Based on taxation the number would be reduced to 13. The final decision after a long and intense session settled on 45.

A somewhat stressed negotiator in a letter to Harley, after the settlement: “I suppose our pilots, by the hand they have in the present negotiation, hope afterwards to steer these northern vessels.”

Harley’s success getting the ratification of the treaty approved, was largely due to the efforts of his chosen instrument, Daniel Defoe. But he prepared the groundwork well before sending his agents to Scotland by encouraging Defoe to use the pages of the “Review” to dampen down criticism of Scotland and encourage favourable views of England.

He also cultivated the support of Scottish nobility and gentry through the secretive deployment to Scotland of a well connected young debonaire man about town, English barrister Barrington-Shute.

He impressed on the English ministers the advisability of appointing the Duke of Queensberry to the post of Lord Commissioner for the deciding session of 1706, taking time to ensure the duke knew he was the chosen one and he expected him to deliver the treaty.

Further consolidating his control over the process and just before the meeting of the Scottish Estates, he wrote to his confidant Carstares who controlled the clergy, “I am making it plain that it is of the highest consequence to the interest of the nation and the island in general terms that this opportunity should not be lost.” He reiterated the same message to the other Scottish commissioners including the refractory Duke of Hamilton.

The input of the spy, William Greg, who had been located in Edinburgh for over a year was important since it was through his regular reports that Harley was kept fully informed of the violence and intrigue that accompanied events in the Scottish parliament which was meeting under the leadrship of the Duke of Argyle before the decision was taken to enter into negotiations for a union.

A few days after the treaty was agreed the Duke of Hamilton wrote to Harley to explain his reluctance to be involved. He said that he opposed the union because he thought: “Scots will never swallow it.”

He followed up with the observation: “It is reported that there are troops coming to the borders to make good the votes we pass. God knows if that looks like an agreeable Union.”

He denied that he encouraged rioting but insisted that he did not want the union implemented with unseeming haste.

The roles and responsibilities of Harvey’s spies in Scotland

John Ogilvie was employed chiefly for the detection of Jacobite plots on the continent and in Scotland.

Fearns, who had once been employed on a judicial circuit in Scotland, was well in with the kirk. In his letter introducing himself to Harley, he wrote: “No other person can pretend to know Scotland so particularly, the people’s constitution, tempers, estates, powers and weaknesses, for there is not one part of the county that I have not relations and clients in it.”

It was, because of this intimate knowledge of Scotland that Harley sent Fearns into Scotland to prepare a list of all the, “chief men in each county,” recording their military strength, political party, religion and attitude toward the succession.

Fearns fulfilled the commission and also wrote to Harley keeping him informed of the proceedings of the estates. All for £5 per month.

Scottish financier, William Paterson, was one of the founders of the Bank of England and the Darien scheme, had for many years been a friend and to some extent a protege of Harley.

His employment was not entirely of Harley’s choosing. In his letter to Harley, Paterson wrote, “it was not my business so much as that of the commissioners of both kingdoms to press that I or somebody who understands finance should be in charge.

Lord Somers and my other friends asked me to speak to you about this matter and if it is not done, it will be understood to be for want of affection to the union, to me, or to both and the doing of it speedily will be more than twice doing it afterward.”

The foregoing is evidence that Lord Somers and the Whig unionists were in a position to see that Paterson was gainfully employed. Harley, who had no problem to the use of a, “financial expert”sent him to Scotland where he took an active part in lengthy committee meetings on taxes, “drawbacks,”and the “equivalent.”

He also reported on important transactions and on the activity of parliament in a perfunctory manner confirming his loyalty rested with the Whigs of the English Government not Harley.

Ogilvie was a Scottish soldier of fortune who had followed James II and was refused indemnity on his return to England. His petition to the queen passed through Harley’s hands, and he was determined to free him for use as a spy. He was sent abroad in 1705 and informed Harley of Nathaniel Hooke’s missions to Scotland.

His expense accounts were large for, as he wrote to Harley: “at court I must make acquaintances and drink a bottle and eat a dish of meat with those I think proper for my use.’’and continually pleaded that, “bricks cannot be made without straw.” Harley deployed him to Scotland in 1707.

But Harley’s “key man” in Scotland was Defoe. There is some indication that the secretary once planned to send him to the continent in 1706, then changed his mind and decided to make use of his moderating influence and powers of observation in the northern kingdom.

During the month of August Harley broached the subject of the trip to Defoe. By the thirteenth of September it was clear, from Defoe’s answer, that he was equipped and ready to start.

characteristically, Harley delayed sending instructions until Defoe, “as Abraham, went cheerfully out not knowing whither he went.” But being a man of infinite resource he drew up an outline of his objectives and submitted them to Harley. They were clear and succinct:

- To inform myself of the measures taken, or parties formed against the union, and apply myself to disable them.

- In conversation and by all reasonable methods to dispose people’s minds in favour of the union.

- By writing and discussion, to answer any objections, libels, or reflections on the union, the English, the court, relating to the union.

- To remove jealousies and uneasiness of people about secret designs in England against the Kirk.

To make smooth the path of union was uppermost in his thoughts and no doubt conversations with Harley had given him an indication of what was expected of him.

Defoe reached Leicester, on 22 September and Newcastle on the 30th, where he was given a financial grant sent there by Harley. He also received instructions which filled in the gaps left in Defoe’s own paper which were:

(a). To disguise all connections with the ministry in England.

(b). To write at least once weekly about the true state of affairs in Scotland.

(c). To convince those with whom he came in contact of England’s sincerity and support for the union.”

Defoe had a very low opinion of Paterson’s work in Scotland. He wrote to Harley that: “He is full of calculates, figures, and unperforming numbers, but I see nothing he has done here, nor does anybody else speak highly of him but in derogatory terms the mannr of which I care not to repeat.”

That there was a real need for last point is evident from the correspondence of James Johnston, a Scot who resided at the English court, who knew Defoe was a master of improvisation, who was best left to implement his own initiatives. Indeed, the way in which Defoe could appreciate the difficulties of a situation and construct plans for meeting them marked him out as a genius and put him in a different category from other agents who preceded or accompanied him.

Thus from October, 1706, until Defoe returned to England almost two years later, Harley continued to receive letters from Defoe at times as many as three each week when exciting events were in progress. Had he been on the spot, Harley could scarcely have gained a more vivid impression of the intensity of feeling, the excitement of action, and of the motives and interests of the champions for and against the union.

Defoe began his work in a truly Jesuitical manner by being, as he said, “all to everyone that I may gain some.” He had “faithful emissaries in every company” and concentrated his first efforts on soothing the Scottish Presbyterians. I work incessantly with them and they go away from me seemingly satisfied and pretend to be informed, but are the same men who plead ignorance when they come to be among their party’s. In judgement they are the wisest weak men, the falsest honest men and the steadiest unsettled people I have ever met.

I mitigation the Presbyterian clergy were greatly perturbed at the prospect of an “unholy alliance” with the Church of England, and at the imposition of oaths and sacramental tests. Thus Defoe attended church gatherings and assemblies and wrote soothing answers to their inflammatory pamphlets, continually warning his friends “that Harley is certainly against the Union.” He also accused Godolphin of lukewarmness, but his letters were remarkable for their continual change of opinion. He elaborated on that with these words :

“I talk to everybody in their own way, to the merchants I am about to settle here to trade . . . with the lawyers I want to purchase a house and land to bring my family. . . . Today I am going into partnership with a member of parliament . . . tomorrow with another in a salt work . . . with the Glasgow mutineers I am to be a fish merchant . . . and still at the end of all discussions the union is essential.” He also called the Scots a “hardened, refractory, and terrible people.”

The third aspect of Defoe’s great service to Harley and to the union was the considerable part he took in thwarting an intended rising in November, 1706. A plot had been formed by certain Jacobites to unite the western Cameronians (a band of fanatical Presbyterians from Dumfries and Glasgow), with some of the Duke of Hamilton’s men from Stirling and Hamilton. These were to meet and join with highlanders who were already in Edinburgh, for the purpose of breaking up the parliament. Defoe, employed John Ker of Kersland to mix in with the Cameronians and persuade the leaders of the folly of the plan. By the end of December the group had disbanded and the union was nearing completion.

On 2 January, 1707, Defoe wrote to Harley, “The Union proceeds apace,” and asked that, “if nothing better can be found I could wish you will please to settle me here after the Union.” Harley was more than willing to accede to this request so Defoe lingered on in Scotland for another year, writing conciliatory articles for the Review, collecting materials for his great History of the Union, keeping Harley informed of the movements which threatened to disrupt the union during its first year of existence.

During these last days of the Scottish parliament Harley remained active. He renewed his appeals to Carstares and to Leven to urge moderation on the Kirk, making free use of the scripture in his condemnation of the zealots and in his praise of the work of his correspondents and he exerted pressure on the Duke of Hamilton, recalling, “the day will com when he will thank me for it. “

Defoe defended the proceedings of the Kirk in the Review, “not that I like them, but to check the ill use that will be made of it in England.”

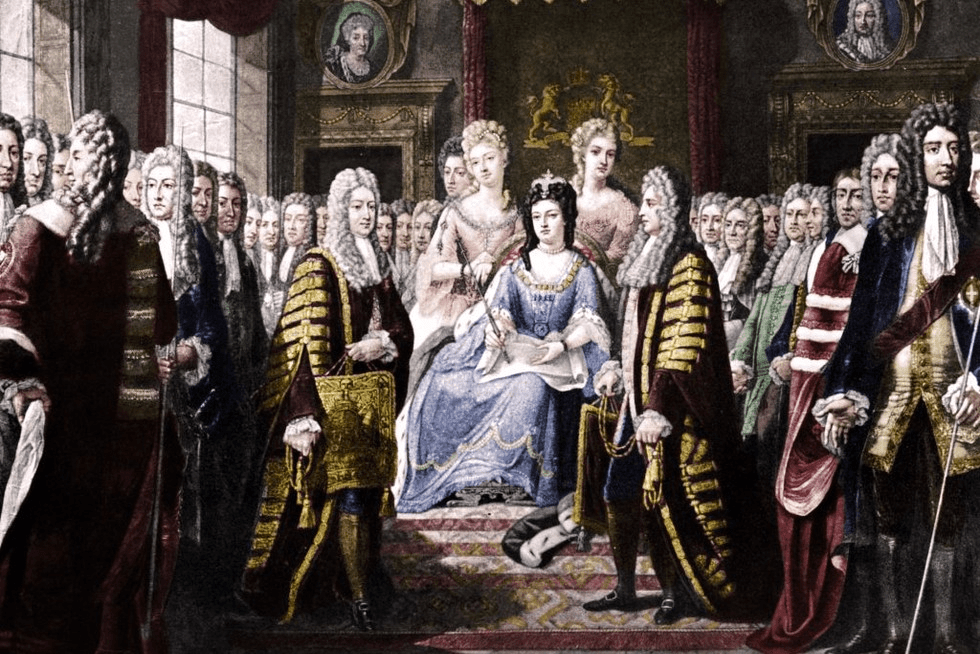

On 16 January, 1707, Queensberry, “touched” the treaty as finally ratified by the Scottish estates. The month following it passed the English parliament. Unfortunately, Harley, who had done so much to bring about the union, lay ill at the time of its completion.

Robert Burns was critical of the Treaty of Union (1707) between Scotland and England. He viewed it as a betrayal of Scottish independence and famously criticized the Scottish elite who signed the treaty, referring to them as:

“a parcel o’ rogues in a nation” who were “bought and sold for English gold.”

A statement to which many Scots still subscribe to 318 years later.