The British view of Scotland 1938-1957

The vexed issue of the relationship between nationhood and the Union pervades recent Scottish historiography, much of which has focused on the kinds of nationalism that developed in response to perceptions of the British Empire.

Throughout the twentieth century political commentators delineated the political, social, economic and cultural landscape through which Scotland’s relationship to the United Kingdom may be understood.

Their analyses contributed to defining a frame of reference through which “Scotland” would be envisioned, an imaginary largely generated from within by Scottish historians discussing “our” accommodation to or rejection of Britishness.

It may prove instructive to compare such inside stories with external notions of Scottishness, these latter ranging from racist caricature, through invented traditions, to academic accounts of Britishness itself.

The ensuing discussion argues that in the emergence of a documentary way of viewing the earlier twentieth century, there exists evidence of a popular British conception in Westminster of Scotland within the union.

This article considers the role of Picture Post, in its time the UK’s most popular photo-weekly, in visualising Scotland during a period of significant economic and social change after the 1930 depression and prior to the advent of mass television.

It explores how the magazine constructed a journalistic space through which Scotland’s encounter with modernity could be understood by the wider nation state. The research involved a contents analysis of many articles and photographs alongside readers’ letters and editorials, and assesses the combination of image, narrative and dialogue in creating perceptions of Scotland.

Picture Post sought to map ordinary lives while implicitly reforming society. Yet, in focusing upon its innovative means of capturing “a new social reality: the domain of everyday life”, via “the punchy radicalism of the photo that shows and the caption that tells”, critics neglected some of its more conservative aspects such as a rather banal imperialism.

When one recent commentator remarked that Picture Post “ventured forth into strange landscapes to try to present to its readers a varied world yet one that all people could feel at home in” he is referring to the sense in which England was that home – it was “strongest in capturing the native strengths of English life.”

The “we” being addressed were always its predominantly English readers. To this extent, its absorption with British national character is one that over-rides and enfolds the delineation of Scotland and the Scots – they are not “other”, but differently British.

Consciousness of Nationhood

Hungarian refugee Stefan Lorant, having edited four German and one Hungarian picture magazine, became founding editor of the British Weekly Illustrated (1934) and Lilliput (1937) before introducing Picture Post in 1938. Prior to this, pictorial publications (Illustrated London News, Sphere, Tatler, Sketch, and Bystander) had catered only to the aristocracy.

Staff were mainly recruited from European anti-fascist political refugees and the editorial content of the publication, up to 1945 emphasised the political significance of its editorial connections, continuity and control.

In 1945 the ownership of the Picture post changed. The new owner supported the concept of a mixed economy welfare state and welcomed Attlee’s Labour victory. However, by 1950 editorial support had swung back firmly to the Tories. There then ensued a period of “vacillating market strategy, frequent changes of editor and mounting losses”, forcing the magazine’s eventual closure in 1957.

Whilst these factors assist the reader clarifying Picture Post’s editorial preoccupations, they reveal no clear ideological breaks in a portrayal of Scotland which consisted of the themes of Empire and Identity.

The depiction of Scottish history was evident only in articles such as those concerning institutional differences from England and coverage of occasional pageants. In the main, it was a narrative conveying the residual strengths of the British Empire, with an increase in royal visits suggesting “concessions to combat the perception of Scotland’s diminishing nationhood.”

Because of its adherence to the overarching sense of Britishness, no coherent idea of Scottish national identity in or for itself emerged. Instead, Scottish articles were conveniently subsumed under a handful of stock categories, each of which played a part in the representation of British culture, in the Geertzian sense as “the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves.” The “we” here was an English one that looked at Scotland.

In the years before, much boils down to the presentation of stereotypes: picture stories about the kilt, ships being built and launched, and miners coming from the “filth of the pit” to “the row of mean, sordid houses”, of “grey fishing villages.” In sharp contrast there is the scenic beauty of the landscape. And there is Glasgow. So Scotland in the round is imagined rather dichotomously, either as a place of “grave beauty” and “wild, infertile districts such as the Highland [deer] forests”; or it is the home of scandalous urban poverty, appalling housing and rickets.

Symbolism of Crown Authority

The symbolism is clear from depictions of George VI opening the Empire Exhibition in Glasgow and the richly ceremonial images of Queen Elizabeth’s 1952 trip to Edinburgh.

A photo-essay of her rain-sodden voyage in the Hebrides was rather less formal, although the opening line of text served to remind readers of the ritual aspect: “To go to Scotland in August has been a habit with the Royal Family since Queen Victoria’s time.”

“Bed Socks for a Queen” sought to make the link between everyday working life in Scotland and the wardrobes of the grand: “Through five generations, this factory in Edinburgh has been making quality footwear for monarch, soldier, sportsman and glamour girl.”

Meanwhile, the effort to convey an impression of Anglo-Scots unity led to some extraordinary tweaking of the historical record. A wartime propaganda piece juxtaposed photographs of Fort George with images of Culloden Moor where the names on the stones are the same names which label wooden crosses in the sands of the Egyptian desert now.

The men of the Highland Division – the men who stormed the Axis lines at El Alamein – are the kith and kin of the clansmen who rose for Bonnie Prince Charlie in the ’45 … neither the men nor the lands they live in have changed … they’re fighting for the same age-old Highland cause.

The saddest part about the Battle of Culloden is the fatalities on either side– nearly 2,000 Jacobites were killed. Only 50 died on the British side.

Scottish military stories were few, although articles about clan gatherings, Highland games, and the aforementioned kilt, in conflating “Highlander” with “Scot”, provided a spurious sense of national singularity.

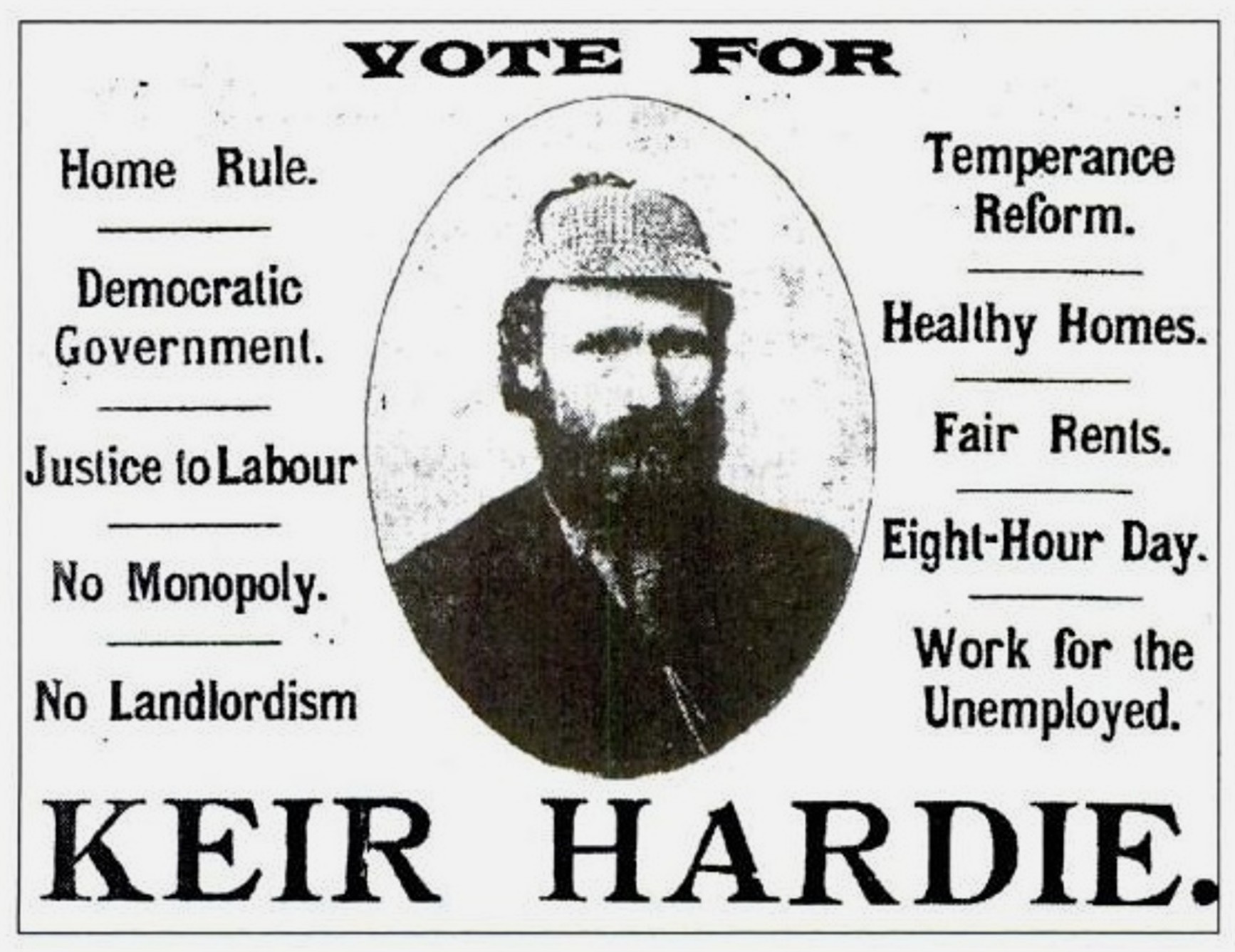

Unsurprisingly, discussions of a separate national identity were few during the war years. However, an intermittent dialogue around nationalism was ongoing. Some Scots blamed Westminster’s dismissal of independence claims for Scotland’s manufacturing industry falling into dereliction.

Yet, railed Compton Mackenzie embracing the Scots audience, “it is our own fault”; so long as “we” submit to London control, we can only blame ourselves for industrial decline, unemployment and rural depopulation.

His 1939 article stressed growing political support for the Nationalists, sporting a photograph of graffiti with the caption “few Englishmen have heard much of the discussion on Home Rule for Scotland – but a plea for it covers almost every bridge on the Edinburgh-Glasgow road.”

Mackenzie’s article unleashed a slew of correspondence. Some questioned the wisdom of publishing material suggesting British disunity in the face of impending world war, blithely adding that “Scotland sends its best to England and we are glad to have them”.

But political nationalism resurfaced very quickly in 1945. Responding to a line in the King’s speech at the opening of the first post-war Parliament that “the special problem of Scotland” would gain ministerial attention, the Nationalist John Kinloch described how the country’s greater resources, output and manpower were accompanied by greater unemployment, poverty and death rates, a predicament he attributed to “Scotland’s subordinate governmental position.”

When subsequently the devolution minded Scottish National Assembly drew up a Covenant supported by thirty-six percent of the Scottish electorate, Fyfe Robertson remarked that “the English press can almost be accused of a

conspiracy of silence” for ignoring important constitutional concerns.

His subsequent investigation asking “Are 2,000,000 Scots Silly?” reported “a new liveliness and confidence largely due to a new awareness of nationality.”

Despite Robertson’s claim of “massive” English indifference, the article sparked a rush of letters, an edited postbag being published under the heading “The Question That Has All Britain Talking.”

For all this, the next month, as “Queen Elizabeth of Scotland” rode in state up the Royal Mile, a decidedly unionist Picture Post praised the protective loyalty of the Royal Company of Archers, contending that “If the Scottish Republican Army were to start any trouble they would soon resemble a row of over-patriotic pin-cushions.”

Sport, Arts and Entertainment

Sports coverage as existed tended towards elitist pursuits – deer stalking and grouse shooting, yachting, rugby union, and – guaranteed to captivate visually – skiing.

Despite its mass popularity, and, indeed, its importance as a lighting-rod for the solidarity of skilled workers, football received scant coverage.

Until a 1955 initiative which saw the launch of “A Great Scottish Football Series” profiling all the major teams in successive issues, the only stories are a piece considering the precarious survival of amateurism, and two negative articles about fan behaviour. “The Football Ticket Stampede” (1952) attempted to explain an incident when 12,000 Glaswegians waiting for tickets for the England v. Scotland game ran amok.

An English sports journalist noted that the Rangers v. Celtic match was traditionally considered “an opportunity to get rid of your empty bottles and vent your religious bigotry.” His article drew indignant responses from many Scots, some accusing the author of being anti-Celtic, others anti-Rangers, others simply arguing that in highlighting the Old Firm’s routine rivalry he was promoting a caricature. “He airs, in true English fashion, the old lie that civil war is our national pastime.” Outside Glasgow, argued another, “people go to see a football match, not two teams representing different religions.”

Moral and Social Issues

For a country supposedly steeped in Presbyterian culture, discussion of religion was rather thin: a photo-essay on the parish kirk of Burntisland, showing “the whole history of the Reformation made permanent in stone”; a quirky tale about the Arbroath padre using ship-to-shore radio telephones to entertain fishermen; and a story about the activities of industrial chaplains questioning the contention that “the Church has lost touch with the workers.”

Nevertheless, complemented by articles on the Iona community’s mission “to bring Christianity to the workers of Glasgow”, this struck a tone very much in sympathy with the magazine’s visual ethos, where locals were pictured engaging in social activity.

Commentary on social issues ranged from health and education to youth crime and immigration. In a debate conducted via the letters page concerning the scourge of “young thugs”, a reader commented give one family a house with modern conveniences; another a room in which there are no sanitary arrangements, in which plaster is falling off the walls and people are forced to sleep four or five in one bed.

Which will be the readier to conform to social laws? Which will produce the delinquent children? This is glaringly obvious in Glasgow, where housing conditions are the worst in Scotland and criminal figures are the highest.

The problems of the “swarming tenement” were being dealt with, but “not always imaginatively” through re-housing schemes lacking in social amenities, as the image of the violence-prone slum continued to cling to the city. Some Glaswegians protested that this was distortion, others that “slums are not an excuse for filth”, while “I’ve had it drummed into me that England is the most democratic country in the world. I find it hard to believe after seeing those slums…. Thank you for opening my eyes.”

Tenement collapse

Post-war responses to social medicine were nevertheless redolent of an innovative approach so that although, for example, a doctor attributed Scotland’s singular failure to show improvement in tuberculosis mortality to “scandalous overcrowding in insanitary, badly-ventilated and sunless houses” and lack of hospital accommodation, Picture Post could show people being encouraged to attend mobile X-ray units using incentives such as raffle tickets and images of futuristic infirmaries.

Elsewhere there were attempts to dispel detrimental cultural stereotypes, with, for instance, the reputedly “inferior” Scottish diet called into question. The education system was revered as being rather better than

England’s. “Little Scotland, with a population equal to Finland, still sends forth from her highlands and islands a steady stream of talent to rule the Empire. This is because she has possessed universal education since the end of the 17th century … and courses of University standard in village schools.”

Similarly, despite Glasgow’s razor gangs, a decline in violent crime, compared to a rise in England, was attributed to differing domestic practices and values: “early discipline in home and school is stricter, the home is a tighter and better-functioning unit, and what is left of regular church-going and Presbyterian morality is still potent.”

In stark contrast to the claustrophobic poverty of the slums the wartime sense of rural Scotland as distant panacea is evident from an advertisement placed by railway companies reading: “What do you seek for your 1940 holiday? A mountain retreat? A lochside resort? A seashore playground? Go to Scotland, where solace comes to weary minds and balm to fretted nerves.”

While similar evocations studied the text of advertisements regularly taken out by bus and ferry companies and holiday resorts, there were also features on yachting on the Clyde, the diverse delights of Arran, the new pastime of pony-trekking, and school adventure holidays. Such escapism was highlighted by photographs of spectacular mountain scenery, majestic sea cliffs and snowbound landscapes.

“Scotland is a lovely place for wildness and beauty, but not in its towns … such a waste to have all those open and often wasted spaces and such huddled towns”, wrote one correspondent.

By 1945 readers were suggesting that the “private wilderness” be handed over to ex-servicemen to farm – “Why does the Government talk about emigration to the Dominions, when Scotland is almost vacant” – and, indeed, land settlement schemes were being developed. The question was posed: “Why can’t the Highlands … be opened up for the Gorbals dwellers?”

“I went on a tour in the Highlands and the conditions are awful”, added another correspondent, “deserted shielings and poverty-stricken crofts, next to mansions whose owners only come in the grouse season and take no interest in their poor tenants”, while a third cited “appalling” unemployment figures and referred to “one long tale of misery” since 1745 with “huge areas denuded of people” to make way for sporting estates.

Crofters’ houses, Stornoway, Lewis, Western Isles, Scotland, 1924-1926

Reconstruction and Modernity

During the inter-war years the Labour Party “pushed the notion of a democratic and radical Scotland which had been under the heel of a corrupt aristocracy … The Scots were a democratic and egalitarian people.”

But the Party did not betray any lasting nationalist commitment and in the immediate post-war years Scottish developments were very much regarded as part-and-parcel of Britain’s wider economic renewal.

Picture Post published a “Plan for Britain” in January 1941. The modernizing vision of “rationally ordered sites and spaces” was embraced by Tom Johnston, appointed by Churchill in February 1941 as Secretary of State for Scotland.

A Labour stalwart, Johnston was “a giant figure …promised the powers of a benign dictator” went on to set up some thirty-two committees and developed planning perspectives in concert with the various socio-economic issues.

Johnston’s single most successful venture, the Hydro Board, was designed to alleviate a British fuel crisis while promoting industrial recovery, re-population and electrification in the Highlands.

Tom Johnston. Father of Hydro power in Scotland

Power generation carried much symbolic weight in the push for reconstruction. However, initial proposals were strongly opposed. A graphic feature on the Glen Affric scheme set the alliance of “beauty lovers” fearing the loss of sanctuary, holiday resort and sporting preserve against the plight of local people.

While the text conveyed a good deal of technical detail, economic and political, regarding the progress of hydro-electrification, its human dialogue came from conversations with the local crofters. Subsequently, a reader wrote in to re-iterate the stark contrast between the lovely landscape and the “abject poverty” and “backwardness” of its inhabitants.

“New hope for the Highlands” ran another article, as “Highland glens light Highland homes.” With dams “surprisingly hidden in the hills”, aqueducts and pylons were “a small price to pay for new prosperity” and relative national efficiency, the more so as a UK fuel crisis loomed.

Re-forestation and ranching added optimism, yet with “roads inadequate beyond belief”, “archaic farming methods” and “progressive deterioration of morale and opportunity” the Highland economy remained precarious, albeit that the sight of Highland cattle presented “A Highland Idyll.”

In January 1955, Picture Post released a special supplement. “Festival Scotland” was both informative and promotional, a shop window of the nation’s attractions and advertisement of its successes.

It provided a potted inventory, incorporating articles on religion, the arts, nationalism, food, fishing, Highland games and Gaelic, but also shipbuilding, shopping, manufacturing, the Scottish joke, history and national identity.

In a foreword, the Lord Provost of Edinburgh noted that he regarded the Edinburgh Festival as “the focus of the post-war revival of Scotland.”

For the tourist, there was advice on “where to go and what to see” from the Secretary of the Scottish Tourist Board as well as guidance on “How to see Scotland”, each itinerary “a gateway to romance” in places “where the dolce far niente of the Mediterranean is matched by the quiet Celtic ways and gentle manners.”

Similarly, Nigel Tranter stressed the urgency of building a Forth river crossing, whether a bridge or a tunnel: “right in the heart of industrial Scotland, precious hours are wasted while cars, lorries and ambulances wait for overworked ferry boats.” Doubtless these writers added weight to debate – much nationalistic, much eccentric yet there is something of the feel of a patrician coterie pontificating from their shared literary quarter in New Town Edinburgh.

Dalmellington, Ayrshire

Nevertheless, a certain gritty realism remains apparent, for instance in a fine portrait of Dalmellington. Here much is redolent of the emerging community studies tradition in British sociology, with its analysis of social segmentation, gendered mores, statistics of religious observation, and anthropological, almost colonial distancing – “Even the “natives” can be sub-divided, for the men who have come down from the now abandoned hillside hamlets … still cling together. You can see at the local dances how much Dalmellington is a man’s world … the young men stood in large clusters talking to each other. There are 1,709 adult communicant members of the Church of Scotland.”

The daily dominance of the mining industry is evoked in the accompanying pictures and their captions, which highlight the day-shift waiting for the bus at 6 a.m., then leaving the pit at 2.30 in the afternoon; meanwhile, the text beside an image of the Saturday dance notes: “it was a grand evening – even for the back-shift who couldn’t get there till after eleven.” There is also a debunking of stereotypes – “curiously enough, Dalmellington does not look like a typical mining village… you do not find there the long, repetitive rows of houses … Instead you see a large country village built around a square … at the edges you find twentieth-century suburban-style houses.” Finally, we read: “There is the insularity of the villages, and, on the other hand, there are the young people’s July excursions to Blackpool.”

This is mid-1950s Scotland in the throes of modernization and a tension between cultural continuity and economic change. Subsequent readers’ letters endorse the “strong community spirit of Dalmellington’s citizens”, extending this sensibility to the city:

Although I have lived in Glasgow all my life I do not think of myself as a Glasgow man. When I was a child the word “home” as it was used by my parents meant not the city tenement, where we lived, but a croft on the Isle of Mull. There may be thousands of Glasgow citizens like me, and perhaps it is because to so many of us our real background is in the Highlands, or the country places, that Glasgow, despite its size, is … like an overgrown village.

Complaints over London dominance of the BBC were being addressed as the network sought to embrace regional broadcasting, they saw no cause for alarm, continuing to represent Scotland as resolutely provincial. (This was, after all, one area of the country where people were still getting their news stories from the press.)

In this imaginary of the nation “Edinburgh is a village where everybody meets everybody else” Characters abound in the Old Town, for it retains many of the qualities of a self-contained community. Neighbours are known to each other.” Glasgow’s “warm-hearted loyalty” draws much praise, while the nation becomes a cultural space in which each major city is given a defining character.

A story about Inverness strikes at the contradictions of capitalism: “Inverness is the great paradox of the Highlands today, the shining example of prosperity and growing population amid economic malaise and depopulation.”

These contradictions are played out in a number of articles concerning the Hebrides. “The Last of the Gaelic” bemoans the “hopeless stand” of a once-widespread language, the “wild, departed spirit” of a dying way of life on Eriskay. Once “peopled by enterprising fishermen”, but now “an island of the old and infirm, with a few horses laden with “creels” to act as transport”, Eriskay’s way of life is being rapidly dispersed by “the dramatic invasion of an air service from the mainland.”

Seaweed-processing came and went on South Uist, where, however, more obviously political concerns had emerged over the proposed siting of a guided missile range. A local wrote to warn that “the entire peace of the island, as well as its crofting and craftsman traditions are likely to be shattered … by the arrival of troops.”

He was not alone: “The Fighting Priest of Eochar” presents “the story of a courageous Hebridean and his fight to save the future of his parish”, the very place that had been so sympathetically photographed the previous year. Again, in the images, there are the expressive rugged faces, mirroring the wind-torn landscape; again, the odd juxtaposition of a precious living on the cusp of change: “On her croft, by the rocket site, a woman finds barbed wire – and wonders.”

Meanwhile, some Hardy images of figures silhouetted against a broad sky suggest a vanishing spiritual purity in a mechanistic industrial age: “the eternal bounty and struggle of life in its simplest, and at the same time, most profound form. I came away from the Crofters’ Isle cleansed and refreshed.”

This dialectic of tradition and modernity, development and dependency, finds broader resonance across the Highland region. “No Future for the Highlands?” asks: “What shall we do to arrest the process of decay … which threatens disaster in the North?” The inner malady of depopulation and ruined cottages. “Some townships will perish within a generation”;

A futuristic shot of Herculean engineering, carries the caption: “Due for completion in 1957, the Loch Shin hydro-electricity scheme employs 900 men, nearly 4/10 of them from the Highlands. But the permanent staff may total only 30.”

Against such brooding concern, “The Road to the Isles” is sanguine. A picture of a woman at a water pump might not suggest progress or engagement in the process post-war industrialization. But the caption suggests otherwise: “Where guidewives gossip in Gaelic, in the old village of Glencoe. Crofting has ceased, and most of then men are employed in the aluminium works at Kinlochleven.”

Vignettes of the triumph of the machine age find their crudest visualization in a photograph of fish being blown sky-high. The caption reads: “Depth charge in the loch. Seventy tons of gelignite are detonated to destroy pike and perch before this water is stocked with young salmon from the hatcheries.”

At the sophisticated end of the spectrum lay the construction of Britain’s first large-scale nuclear fast reactor at Dounreay, a site chosen “because any possible radiation effects can be more easily checked in a sparse population.

Dounreay: Radioactive waste was disposed down the Shaft from 1959 to 1977, when an explosion ended the practice

” As with the guided missiles on South Uist, the motives for scientific advancement concerned strategies other than the strictly socio-economic. They indicated the continuing role of Westminster government in the political management of change. External control of the Scottish economy was welcomed as inward investment.

Where Clydeside shipbuilding, like other heavy industries, had figured in the wartime propaganda effort and “men who build the ships that sail the seven seas” were still honoured reflecting the mood of post-war optimism in its embrace of manufacturing as the route to economic buoyancy.

Promotion of the “American Invasion” was accompanied by photos of the Queen visiting an adding machine factory, a “bonnie Scots lassie” checking clock mechanisms, more “Scots girls at work on assembling components of electronic devices”, rubber footwear, mechanics at an IBM plant. Here were the newly “thriving towns” of the Central Belt, its oil refineries, rolling mills, and, indeed, fresh orders for the shipyards.

Dounreay: shaft cleared of waste after huge explosion

“Let Glasgow Flourish” brought characterful resilience to the fore: “Thrice within a couple of centuries, Glasgow has reeled from the impact of economic forces beyond its control. Each time it has recovered. Now it faces the hazards and opportunities of a new industrial age…. Here is vitality, energy in abundance. Here is the Vulcan’s forge of the North.”

Cue pictures of busy quaysides, locomotive and tobacco production, golf club manufacturing, and “a pavement of biscuits” on the conveyor belt at the Glengarry Bakery, churning out “a quarter of the total chocolate biscuit

output of Britain.”

In the “breath-taking panorama of Glasgow”, was an optimism underpinned by commitment to adaptation and diversity. And not just in the big conurbations. A social commentator said “Kilmarnock has been called “a planner’s delight, ready-made for prosperity.” Where else can one find such a remarkable variety of industry? With full employment, progressive businessmen, and a rigorous spirit of craftsmanship, its future seems secure.

“But is the town really slump-proof?” With images of tractor assembly lines, shoe patterns, distilleries, men at Glenfield and Kennedy, hydraulic engineers, “leading organisation of their kind in the British Commonwealth”, and sub-heads such as “Cushioned against depression”, the answer was a resounding Yes!

Mass production without tedium, in the highly modernised assembly department of British Olivetti, Ltd., at Queenslie Industrial Estate, a young lass from Airdrie, dexterously plays her part in the building of a portable typewriter. Many of these machines go to Australia and New Zealand; also to Africa.

“The Hospital of the Future” provided “an exclusive peep into the first complete new hospital to be built in Britain since the war” at Alexandria. Futuristic architectural images accompanied the “new design for living – for patients and hospital staff.”

The fight against urban health problems was still being conveyed by photo-journalists with characteristic vigour. In March 1957, a double-page feature showed long queues awaiting X-raying under the banner “Glasgow Blasts TB.”

TB Epidemic in Scotland. X-Ray Coaches deployed from all over the UK to Assist

Caused by overcrowded houses and poor diet.

While nationalization, new towns, engineering projects, tourism and Edinburgh Festival culture were promoted as the New Scotland, so the meaning of nationhood came under fresh scrutiny as unionist-nationalism declined.

Contradictions surfaced over the presentation of national identity, and, relatedly, land use and access, that are still important today. “An American in Scotland” opined “they have mountains like the Alps and roads like Burma”.

while the historical Scotland author, Nigel Tranter provocatively argued that a new road should be built through the Cairngorms. It was only, he said, “the remoteness of legislators, hunting, shooting and fishing interests, those benefiting from other roads and the sanctity-of-the-wild enthusiasts” that were preventing the construction of “a glorious, a darling road.

Likewise, when a reader responding to an article on the “strange collapse” of Scotland’s former aviation industry pleaded “Let us concentrate on our tourist industry and have more beaches, better roads and better hotels rather than more factories, with their dirt and smoke”, he was effectively arguing for the preservation of an invented tradition – romantic tourism – within a framework of modern industrial development. In grasping the horns of a dilemma first captured visually through the hydro-electric debate, both writers were perhaps more prescient than they imagined.

Typical Tourist photo

Conclusion

1955 was a pivotal point, for it was in this year that two significant events occurred: a General Election on 26 May in which the Unionist party reached its zenith of 51% of the Scottish vote, never to be achieved again as the end of Empire, decline of sectarianism and, latterly, Tory anglicisation conspired to create an agenda for national identification dominated by debates between Labour and the Nationalists

A complete run of Picture Post is available in the National Library of Scotland. A fully searchable archive may also be consulted via http://www.gale.cengage.co.uk/picturepost (Accessed Nov. 2012)

Andrew Blaikie is Professor of Historical Sociology, Department of History, University of Aberdeen.

Gorbal life

Leave a comment