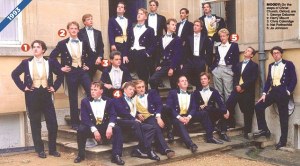

Andrew Dunlop (R)

Andrew Dunlop (R) Four comrades

Four comrades

18 March 2012: Cameron’s recruits Andrew Dunlop (SPAD) to his referendum team

Scotsman, Dunlop 52, was quietly recruited by Downing Street as the Prime Minister’s personal adviser on Scottish affairs, with a special remit to help defeat independence. He is a genuine greybeard in his 50’s, several years older than the Prime Minister.

Dunlop who graduated in economics from Glasgow University has spent most of his working life south of the Border. He is a well-known right wing Thatcherite in the Conservative power structure.

His CV includes spells working for George Younger and John Major, as well as the discredited and subsequently banned Atlantic Bridge charity run by Liam Fox’s friend Adam Werrity.

He is also a councillor on Horsham District Council and lives in the exclusive commuter village of Partidge Green, on the edge of the South Downs National Park.

By 1988, he graduated to Mrs Thatcher’s inner circle as one of the seven members of her “policy unit”, specialising in defence, employment, tax reform and Scotland.

In that capacity, he played a key role in discussions over the introduction of the hated Poll Tax in Scotland in 1989 – a year earlier than the rest of Britain. After leaving No 10 Downing Street, he became the founding member and managing director of top lobbying firm Politics International.

Yesterday SNP MSP Stuart Maxwell said: “Questions must be asked on what role a young Mr Dunlop – a policy adviser to Thatcher in tax reform and Scotland in the late Eighties – had in the implementation of the Poll Tax in Scotland.

It is also interesting that the Prime Minister has employed a so-called expert on Scotland who lives in the south of England. The people of Scotland deserve transparent politicians, not Tories who don’t even live in the country they hope to rule over. Cameron’s new Thatcherite appointment will result in even more people opting for home rule with independence.” http://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/308827/Questions-over-Cameron-s-new-independence-adviser-s-link-to-poll-tax

24 March 2012: Rich Boy Andrew Dunlop – watches the pennies – caught abusing his free council parking permit

Mr Dunlop has already found himself embroiled in controversy in his new role after it emerged he had been abusing his free council parking permit. He was avoiding a £7.50 a day charge by leaving his £30,000 Jaguar XF in a council- car park near Horsham station before catching the London train. Yesterday, after being caught out by his local newspaper, he was forced to apologise and offered to repay the charges. He said: “Four weeks ago I started commuting daily to London to attend a new full-time job at 10 Downing Street. “On a limited number of occasions, when I was not on council business, my car has been parked in an HDC car park adjacent to the council’s offices. “When it was brought to my attention by a council officer that car passes should only be used exclusively on council business, I immediately refrained from using this car park.”

http://www.wscountytimes.co.uk/news/local/parking-exclusive-hits-national-headlines-1-3662200

2 July 2012: The attorney general, the charity and a lucky escape

A return for Liam Fox as he steps back into the harsh glare of public debate with words on Europe to cheer the Tory right. All seems clear ahead. And yet he cannot quite leave what’s behind behind. For there is a epilogue to the saga of the Atlantic Bridge, the faux charity he chaired. It was wound up last year after complaints to the Charity Commission that its business was not charity but politics.

The Trustees were Professor Patrick Minford, of Conservative Way Forward, Lord Astor of Hever and the Tory lobbyist Andrew Dunlop. Forgive them, said the commission; they didn’t know the law governing their responsibilities. And with the release of a supplementary report, we have a better sense of one of the factors the commission had to consider in deciding what to do about the misapplication of charitable funds and the possible recovery of those funds from the trustees themselves.

For “such proceedings can only be brought with the consent of the attorney general”. No evidence of bad faith was found, the commission makes clear, so perhaps the issue is moot. But it would have been fascinating to see what Dominic Grieve would have done, had the hot potato of Tory charitable shenanigans reached his desk.

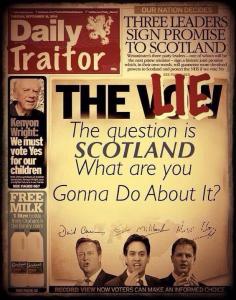

September 2014: Scottish Independence Referendum – The Unsettled Will Of The Scot’s – The Inside Story Of The Unionist’s Campaign Of Fear

When scholars come to write the history of Scotland’s 2014 independence campaign they may conclude the United Kingdom was saved by an opinion poll. It was the startling lead for a referendum Yes vote reported by YouGov on the evening of September 6 that finally shattered the complacency of UK political elite that had previously failed to realise the 307-year-old union between England and Scotland was really at risk.

The extraordinary story of how the dream of Scottish independence – long nurtured by a third or fewer Scots – suddenly turned into an existential threat to one of the world’s premier powers is a lesson for leaders everywhere of the danger of taking voters for granted.

And while the No campaign eventually won by a margin of 55 to 45 per cent, the panic that engulfed the Westminster elite as polling day approached laid bare the fragility of the union and raised searching questions about the way mainstream politicians dealt with the threat.

It is a mark of how overconfident pro-union UK politicians were about the possibility Scots might vote for independence that many initially welcomed the prospect of a referendum. Thursday’s vote had its roots in the Scottish National party’s stunning success on May 5 2011, when it won a majority of seats in Scotland’s devolved parliament.

During its previous minority administration, the SNP under Alex Salmond, first minister, had put independence on a backburner. Now opponents thought Salmond, long a proponent of gradual progress toward independence, would be forced into a referendum before he was ready – and would suffer a defeat that would drain the SNP of its raison d’être.

“I sat there watching television and found myself cheering on the SNP,” said one Liberal Democrat minister in the UK government, recalling the night the Scottish election results came in. “If they were going to win, the best we could hope for is that they got a majority and were forced to hold a referendum and finally put the independence issue to bed.”

The next day, David Cameron, UK prime minister, immediately conceded that Scotland should be granted an independence referendum if the Scottish government wanted it. It was a decision some colleagues would later bitterly criticise. Other states such as Spain have been much less accommodating towards secession demands.

“When I talk to my counterparts in other countries, they cannot understand why we had a referendum at all,” says one UK minister. “Where were the crowds on the street demanding such a thing? Why did you need to do it?”

But other UK prime ministers including the late Margaret Thatcher had previously accepted that Scotland, an independent nation until its parliament voted to unify with England’s in 1707, would have the right to leave the UK if it opted democratically to do so.

For a long time, the threat to the UK unity seemed small. The 2011 SNP victory was followed by an 18-month phoney war dominated by argument over the referendum process.

Cameron and his allies were exasperated by what they saw as quibbling over details. They wanted a clear and straight forward Yes-No vote on independence, fearing that allowing a third question on greater devolution within the UK – which polls made clear would be the most popular option among Scots – would allow Salmond to claim victory even if independence was rejected.

To secure a single question referendum, Cameron gave in on a series of other points, including on the framing of the question. This allowed Mr Salmond to campaign for a Yes vote. Perhaps most importantly, Cameron also allowed the Scottish government to decide the timing of the vote. Eventually set for September 18 2014, this gave the SNP plenty of time to build its case.

As recently as the summer, senior No campaigners were more concerned about the size of the victory than the fact of it. “We need to get 60 per cent if we are to avoid a neverendum,” said one campaign insider several weeks before the vote, referring to the possibility of another ballot being called within years or even months in the event of a close result.

All this time a broad Yes movement was developing, reaching far beyond traditional SNP support. At first it seemed to have little impact. The official pro-union Better Together campaign pummelled the SNP over the uncertainties of independence. The party’s 667-page vision for an independent nation, published in November 2013 and including promises of better childcare, lower taxes and more generous social security, brought no immediate boost to nationalist support.

Scottish Independence Referendum – The Unsettled Will Of The Scot’s – The Inside Story Of The Unionist’s Campaign Of Fear

In early 2014, the No camp lead started to narrow. So pro-union politicians prepared what they hoped would be a fatal blow to Salmond’s plans.

Many who were in the conference room in Edinburgh where Osborne on February 13 ruled out a post-independence currency union thought that a killer blow was exactly what had been delivered. Speaking in front of a plate-glass window looking out at Edinburgh’s Castle Rock, the UK chancellor targeted the biggest weakness in the SNP’s economic case – its claim Scotland would continue to use the pound as it does now, a promise dependent on London’s consent.

Osborne was backed by the leaders of all three main UK parties – and given unprecedented public support by Sir Nicholas Macpherson, the Treasury’s top civil servant.

The assault, delivered by a Conservative chancellor deeply unpopular in Scotland, had mixed results. The SNP dismissed it as bullying and bluff – and polls showed many voters in Scotland agreed. But Osborne insists he was right and that this week’s No vote vindicated his strategy of highlighting the risks of independence. “It’s a No campaign, so of course it’s going to be negative,” the chancellor has said.

Meanwhile the Yes campaign was developing into a grassroots movement far more energetic and organic than Better Together could muster. SNP strategists were building on the databases and tactics that had delivered the 2011 landslide. Their strategy aimed to first persuade voters that Scotland could be independent, next that it should be, and finally that it must be.

Still, Westminster was untroubled. Two months ago, Cameron had dinner with a close friend from the corporate world, according to one senior business figure. Of all the things in his prime ministerial in-tray, the business figure recalls Cameron saying, Scotland was “the least of his worries”.

Cameron and Osborne departed for their summer holidays in August in confident mood. Osborne was heard to remark breezily to colleagues that he would “take 60-40” as a final result.

Polling advice provided by Populus suggested the No lead was solid and backed up Osborne’s conviction that Better Together’s focus on the drawbacks of independence rather than the benefits of union was working to stop wavering voters following their emotions and voting Yes.

But public opinion was turning toward Yes. Some credited Salmond’s strong performance in a second televised debate against Alistair Darling, former UK chancellor and Better Together leader. There he warded off challenges on currency and scathingly portrayed Darling as being “in bed with the Tories”, and the National Health Service as under threat from continued union.

By the weekend of September 6-7 there was panic inside Number 10, while Cameron was obliged to leave London with a knot in his stomach to stay with the Queen at Balmoral. Alexander and Danny Alexander – the Treasury minister overseeing the Lib Dem campaign – reported that the momentum to Yes might become unstoppable. That fateful YouGov poll put the Yes side ahead.

“We knew a poll was coming which would give the Yes side a lead – it turned out to be YouGov in the Sunday Times. We were at a point where we had to reframe the campaign,” Douglas Alexander said later.

Frantic discussions took place over that weekend between “the two Alexanders” and Andrew Dunlop, who by now were the principal players in the fight to save the union. Dunlop hit the phones to try to corral a business onslaught, joined by Danny Alexander and Alistair Darling. By Wednesday a trickle of companies led by Shell and BP were speaking out; by Thursday there was a torrent.

Cameron himself turned up the heat on business leaders to intervene in the debate, hosting a reception on September 8 in Downing St. “He left us in no doubt we should speak out,” said one chief executive who attended. The prime minister was also hitting the phones. “Those phone calls can be very persuasive,” said one business figure familiar with the operation.

The result was a wave of business opposition to independence, with companies such as Aviva and Prudential coming out to bat on the prime minister’s behalf, although a few – including J Sainsbury, National Grid and Tesco – could not be persuaded.

On the Thursday before the referendum five Scottish-based banks said they would move their registered headquarters south if there was a Yes vote. But the orchestrated campaign also risked fuelling Scottish resentment of Westminster. Salmond loudly protested against Downing St “scaremongering” and blamed a hostile BBC for playing along.

Even the Queen joined the fray, her media advisers orchestrating a “chance remark” to a churchgoer near Balmoral that Scottish voters should “think very carefully about the future”. Buckingham Palace said she was strictly neutral but royal watchers had little doubt about the Queen’s concerns about the breakdown of the union, despite Salmond saying he looked forward to her becoming Queen of Scots.

The fightback also had a new public face: Gordon Brown. The former Labour prime minister had been on the fringes of the No campaign for months, but his refusal to work with the Tories and tense relations with Darling, his former chancellor, meant that he often operated alone. Now he was brought centre stage, making the “positive case” for a No vote: promising a swift transfer of new powers to the Scottish parliament to demonstrate to wavering Labour voters that a No vote did not mean “no change”.

The combination of economic scare stories and promises of future power seemed to work, while it proved harder than independence campaigners had hoped to mobilise the disaffected urban population.

By the last days of the campaign, pro-union leaders were increasingly confident they could hold the line. On Friday morning they were shown to be right. The victory when it came was clear. But by voting for independence, 1.6m Scots graphically demonstrated the depth of popular discontent with Westminster rule. For pro-union politicians the two-year campaign race ended not in a triumphant last lap but a panicky late sprint over the winning line. This was far from the emphatic reaffirmation of union they had expected.

Culled from Financial Times http://www.punchng.com/politics/scotland-how-britain-nearly-lost-a-united-kingdom/

Leave a comment